A recent study has revealed that a hereditary disease that produces high cholesterol levels is often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a hereditary disease that affects as many as 1 in 300 persons worldwide, resulting in a global population of more than 25 million people.

If they are not treated with cholesterol-lowering medicines like statins, they are at a higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

High Cholesterol Condition And What If It’s Left Undertreated

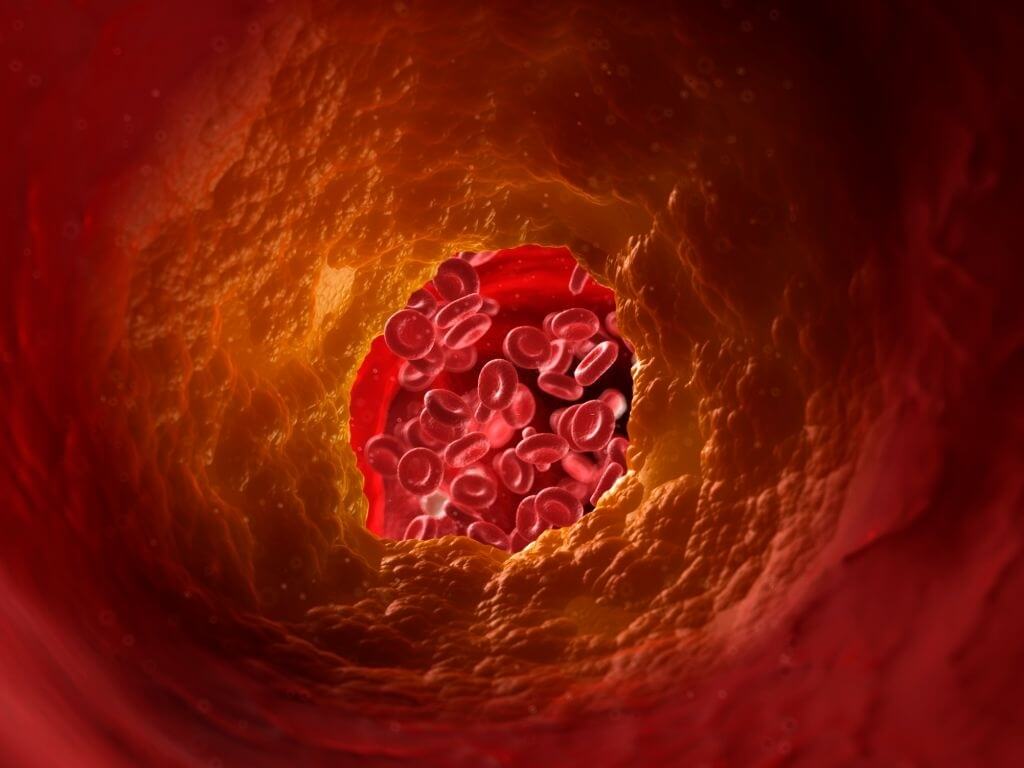

Under-treatment of cholesterol can be a big issue once the level of the same is higher compared to the permissible limits. However, as per experts, one needs to go for a quick treatment as it may be troublesome for the blood flow leading to cardiac arrest. Those who neglect the level of cholesterol may be at a higher risk of heart failure. The experts recommend people keep a regular check on the same.

Investigators led by researchers have published the most accurate global snapshot to date of FH and how it is managed. It highlighted how the condition is being diagnosed too late in life, the need for more intensive cholesterol-lowering drugs, and how women’s diagnosis and treatment lag behind men’s.

Their findings, which were published in The Lancet, are the first to emerge from the European Atherosclerosis Society Familial Hypercholesterolemia Studies Collaboration, which compiled data from over 42,000 adult patients with FH from 56 countries (FHSC).

“As an inherited illness, FH is recognized too late, on average in the mid-40s in the FHSC adults in the united states, meaning that many years elapse before individuals are recognized and therapy is initiated,” said Dr. Antonio Vallejo-Vaz, principal author of the research from Imperial’s School of Public Health. In this scenario, there is also a possibility that a late diagnosis may lead to missing out on opportunities to treat other cardiovascular risk factors that tend to develop as individuals grow older. It is essential that FH must be better identified to discover individuals who are impacted considerably sooner.”

Researchers discovered that FH diagnosis is typically delayed, with fewer than half of adult patients detected before the age of 40. According to the registry, the median age of diagnosis for the nearly 30,000 people for whom data is available was 44.4 years, with one in every six already having heart disease. The majority of individuals on lipid-lowering treatment were using a statin. However, few people were using the maximum dosages of statins, and only about one in five were taking several lipid-lowering medications. Despite having greater LDL-C levels from age 50, women were less likely than males to get the highest dosages of statins or combination treatment.

LDL-C values below 1.8 mmol/L (70 mg/dL) were achieved by less than 3% of patients on therapy, and women were less likely than males to achieve these levels. “The difficulties of FH were emphasized by the World Health Organization (WHO) Report on FH in 1998,” stated Professor Kausik Ray of Imperial College’s School of Public Health, who also heads the FHSC registry. However, there has been little progress in adopting the suggestions to solve these issues.

When a person is diagnosed with FM, the FHSC study underlines the importance of early screening of family members (called an index case). Comparatively to index cases, people identified by family screening were younger and less likely to have additional cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and clinical coronary artery disease. There is still a lot of research which is underway, and we can expect more prominent breakthroughs in this topic. Further discoveries can change the way we look at cardiovascular diseases.