A group of University of Alberta scientists has discovered that an enzyme identified as BAD plays an unanticipated function in the capacity of cells to move in the brain, a discovery that could help scientists better understand how ovarian diseases spread.

Elevated concentrations of BAD have already been linked to better mortality in women with breast cancer, according to Going and her colleagues. The researchers looked at BAD’s involvement in regular biology to figure out how and why.

It May Help Us Understand How Breast Cancer Spreads

Among the diseases with a large number of patients those who suffer from breast cancer also hold a considerable share. To counter the cells that spread cancer it is necessary to know how they act in different conditions and what can be the option to prevent them from moving to other areas.

This study was focused on these concerns only and after a long study and analysis of various samples now the experts have reached a stage where they know how it can be prevented from spreading in the body.

AD stands for “BCL2 associated agonist of cell death” and plays a variety of activities in the brain, including triggering the apoptotic cell process of death. According to the latest study, it also plays an important role in cell motility, giving the enzyme an excellent candidate for further investigation.

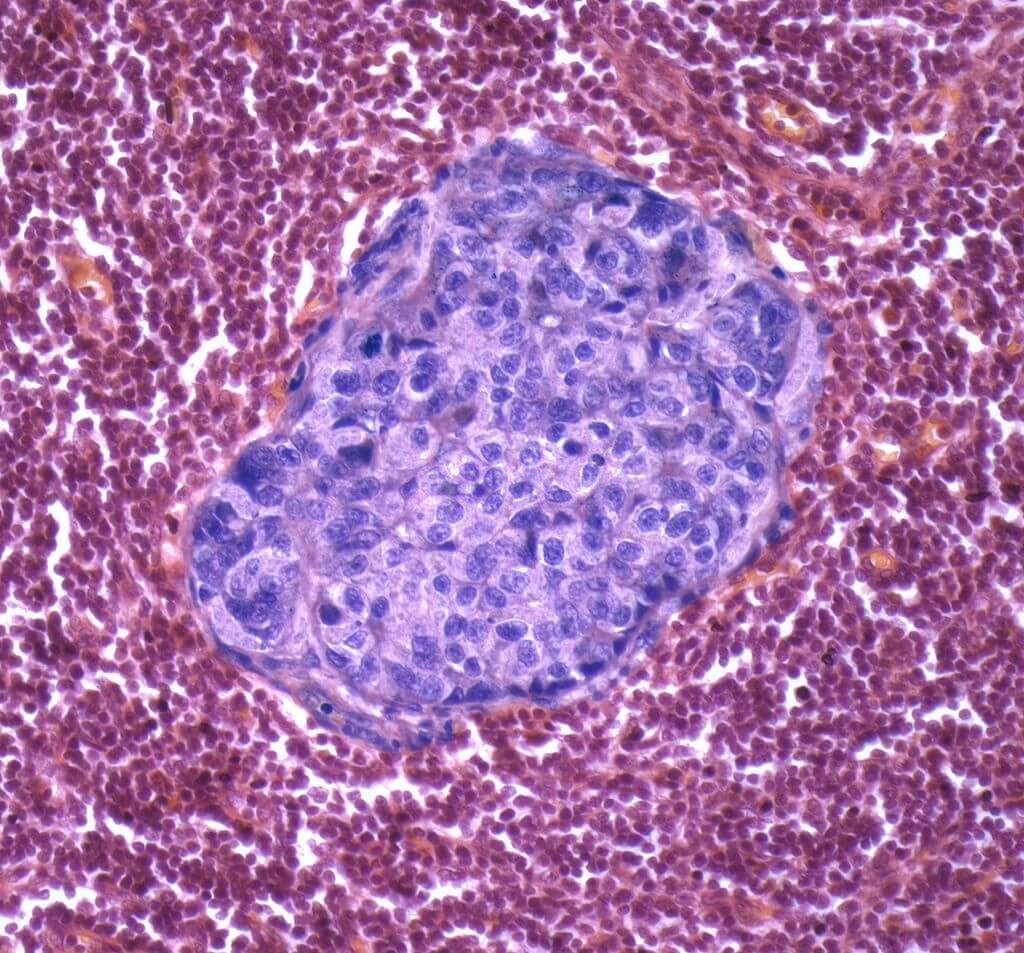

Throughout adolescence, breast epithelial are busily forming a network of channels that will eventually be employed for milk glands, and the lymphocytes are extremely migrating. Cell migration ends after the duct network is created. The activation of migration mechanisms is what promotes metastasis, and Going & her colleagues wanted to learn more about BAD’s function in the cycle to understand better it.

“All of these fingers come out but they have no grip; it’s like a climber trying to scale a wall without chalking up their fingers,” said Going. “If we can deplete that traction from a tumor cell that’s trying to migrate out of the breast, perhaps we can inhibit metastasis. That’s what we’re trying next.”

The relevance of phosphorylated, the mechanism by which a phosphorus atom binds to a molecule, was one of the main discoveries they made. The cell cannot migrate if BAD also isn’t activated in normal pubescent cells. The cell does develop protuberances to aid movement; however, these protrusions are unable to grasp something, leaving the cell stagnant.

The mammary gland’s growth is slowed if BAD is altered so that it can’t be phosphorylated, according to researchers. Signal proteins assemble at protruding locations and drive the synthesis of a specific protein required for the formation of proper cellular protuberances.

The mutant BAD stops the generation of protein that is essential to make the pushing protuberances.

Scientists may be able to find even more sophisticated strategies to restrict cell motility by pinpointing those upstream enzymes.

“If BAD is the quarterback that says we’re going to run or we’re going to stop, it’s a good target to be looking at,” said Going. “If you want to control the game, you want to have control of that key piece. This discovery shows that BAD can have these multiple roles it wears multiple hats and these are new roles that we’re trying to explore with respect to cancer and metastasis.”

The research is published in Nature Communications with the title “BAD governs mammary gland morphogenesis via 4E-BP1-mediated regulation of localized translation in mouse and human models.”

The next phase in the experiment is to investigate the effects of dephosphorylating BAD to determine if it can prevent metastases by regulating protuberances and guaranteeing the cell can’t grab everything and migrate through the system.