Colorectal carcinoma is the 3rd least frequent cancer in the United States and the 2nd largest source of cancer-related mortality.

Despite the fact that colonoscopy screenings are an excellent technique to identify and treat colon cancer by removing polyps, colorectal cancer remains to be a leading cause of death. Existing medicines, according to DuBois, have poor effectiveness for lengthy life for individuals with phase 4 cancer.

Colorectal Cancer Research Gains Ground

“The work is the first time we are aware of that someone has shown how a checkpoint inhibitor is regulated due to loss of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene function,” said Raymond N. DuBois, M.D., Ph.D., director of Hollings Cancer Center and a senior author of the study.

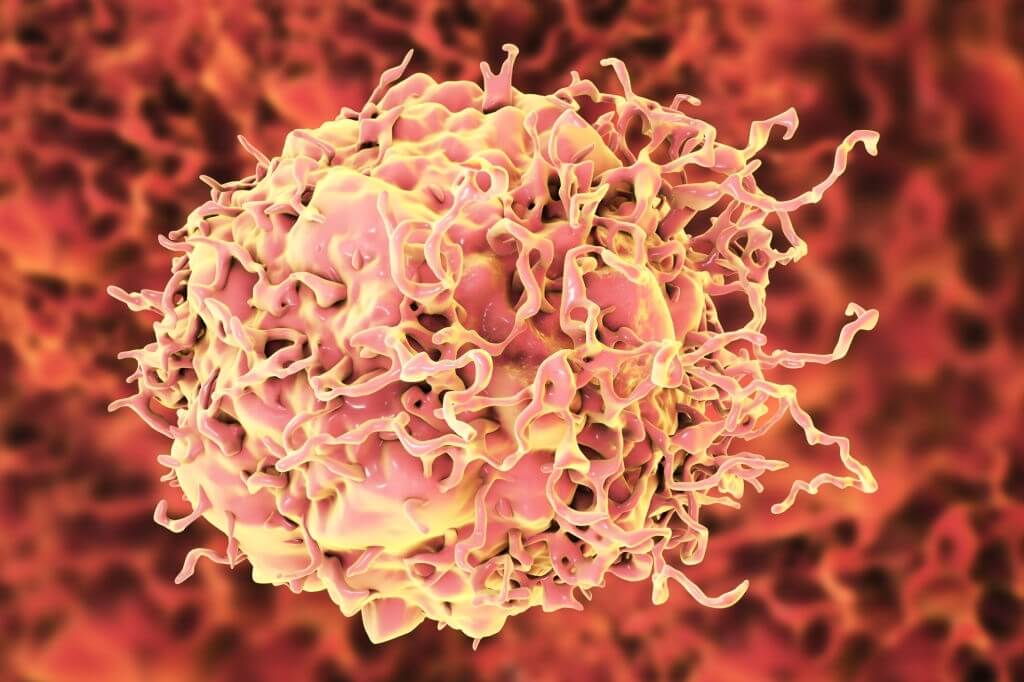

Scientists at the University of South Carolina’s Hollings Cancer Center found a new method that explains how a specific gene mutation could allow tumors to elude identification by the innate immunity in colorectal cancer sufferers. The research, which is reported in Oncogene on July 22, is the latest current instance of Hollings’ cooperative science.

This new method can help early diagnosis of this cancer and provide some additional time to experts to have a better line of treatment to save the patient. Though some more researches are needed, this method can surely get better recognition among experts said one of the members of this research team while explaining the utility of this new method for common patients of this disease.

The DuBois group has been studying the genetic pathways that underlie colorectal cancer start, development, and development in order to develop new preventative and treatment options in this field.

“PD-L1 levels are elevated in a variety of human cancers, including colorectal cancer, and this sometimes leads to a poor prognosis,” DuBois said. “We know that high levels of PD-L1 on the surface of cancer cells are related to the tumor’s ability to evade the immune system.

However, the exact role PD-L1 plays in colorectal cancer is unclear. Some reports in the literature present conflicting results as to whether the presence of PD-L1 is indicative of a better or worse cancer prognosis.”

They also discovered a novel method by which APC alterations allow colonic cancers to elude immune response identification via an immunotherapy route and improved T-cell resistance. “These results expand our understanding of the role of APC in colorectal cancer and pave the way for developing new target drugs as possible b-catenin inhibitors for use as alternative immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer therapies,” added DuBois. The novel treatments may be incredibly useful in halting the development of colorectal cancer at a preliminary phase.

“This discovery represents the first evidence that we know of demonstrating that the loss of APC results in stimulation of PD-L1 in colon cancer cells via the b-catenin complex binding to the PD-L1 promoter,” DuBois said.

Earlier animal experiments have shown that the lack of APC leads to the creation of adenomatous polyps, which are noncancerous tumors that can turn malignant over time.

The APC molecule may form a compound with the protein -catenin, which is important for cell therapy renewal and organ repair. Several tests conducted by DuBois’ team revealed that -catenin is essential for APC mutations and elevated concentrations of PD-L1.

“We know there are other pro-inflammatory pathways that inhibit the ability of the immune system to attack tumor cells that are different from the immune checkpoint pathway. We are using animal models to test compounds that can block those inflammatory pathways. Now we are using those in addition to checkpoint inhibitors, and the combination of both approaches could turn out to be a game-changing and effective new therapy.”